Evolution of RNN

Early Inspirations (Before Modern RNNs)

1901 – Cajal: Observed “recurrent semicircles” in the cerebellar cortex.

1933 – Lorente de Nó: Identified recurrent reciprocal connections (vestibulo-ocular reflex).

1943 – McCulloch & Pitts: Proposed neuron model with cycles → theoretical basis for recurrent loops.

1949 – Hebb: Reverberating circuits as mechanism for short-term memory.

1960–1961 – Rosenblatt: Closed-loop cross-coupled perceptrons, Hebbian learning.

1971 – Nakano: Published recurrent-like networks.

1972 – Amari: Developed similar models.

1974 – Little: Contributions to recurrent statistical models.

1975 – Sherrington & Kirkpatrick: Spin glass (SK model) → foundation for Hopfield.

1982 – Hopfield: Introduced Hopfield network with binary activations.

1984 – Hopfield: Extended to continuous activation functions.

Modern RNN Era

1986 – Jordan: Proposed Jordan network (context from output layer).

1990 – Elman: Introduced Elman network (context from hidden layer).

1993 – Schmidhuber: Neural History Compressor → solved “Very Deep Learning” (>1000 unfolded layers).

1995 – Hochreiter & Schmidhuber: Invented Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) → solved vanishing gradient problem.

1997–2000s: LSTM gradually became default RNN.

1997 – Schuster & Paliwal: Introduced Bidirectional RNN (BRNN).

2006 onward: BiLSTM revolutionized speech recognition, text-to-speech, and machine translation.

2014 – Cho et al.: Proposed Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) as simplified LSTM.

2014 – Sutskever, Vinyals & Le: Seq2Seq encoder-decoder RNN → foundation for attention mechanisms.

2015–2017: Attention-based RNNs → stepping stone to Transformers.

2018 – Peters et al.: ELMo → deep stacked bidirectional LSTMs for word embeddings.

Specialized RNN Variants & Extensions

Hopfield (1982, 1984): Recurrent associative memory networks.

Kosko (1988): Bidirectional Associative Memory (BAM).

Jaeger & Haas (2004): Echo State Networks (ESN) → fixed random reservoir + trained output layer.

Socher et al. (2011–2013): Recursive Neural Networks for NLP tree structures.

Graves et al. (2014): Neural Turing Machine (NTM) → RNNs with differentiable memory.

Graves et al. (2016): Differentiable Neural Computer (DNC), extended NTM.

2018+: PixelRNN, IndRNN, HRNN, MTRNN, etc., explored new structures (spatial, hierarchical, multi-timescale).

Summary

RNNs evolved from neuroscience-inspired feedback loops → Rosenblatt’s recurrent perceptrons → Hopfield’s associative networks → Jordan/Elman cognitive models → LSTM and BRNN breakthroughs → GRU and Seq2Seq → attention-based RNNs and ELMo → and finally toward specialized and hybrid architectures that paved the way for Transformers. Each step improved handling of temporal dependencies, memory, and scalability.

Evolution of Machine Translation (General Level)

Rule-Based MT (1950s–1990s)

Relied on dictionaries and hand-written grammar rules. Worked for controlled domains but was brittle, labor-intensive, and poor at handling real-world language diversity.

Statistical MT (1990s–2010s)

Shift to data-driven methods: learning from large parallel corpora. Used phrase tables and probabilistic alignment. Provided better fluency than RBMT, but struggled with rare words and long-range dependencies.

Neural MT – Early RNN Models (2014)

Encoder–decoder architectures (Cho et al., Sutskever et al.) replaced phrase tables. For the first time, translation was modeled end-to-end with neural networks. These handled variable-length sequences but were bottlenecked by compressing everything into a single vector.

Attention Mechanisms (2015–2016)

Bahdanau et al. introduced soft attention to allow models to “focus” on relevant parts of the source sentence. Luong et al. refined attention (global, local, input-feeding). This improved translation of long sentences and rare words, while also providing more interpretable alignments.

Scaling NMT (2016 – GNMT)

Google’s GNMT added deep stacked LSTMs, wordpiece tokenization, parallelism, and production optimizations. Reduced translation errors by ~60% compared to phrase-based MT, bringing NMT into real-world deployment.

Transformer Era (2017 → Today)

Vaswani et al.’s “Attention Is All You Need” replaced recurrence with self-attention. Faster, more scalable, and better at capturing long-range dependencies. Became the foundation for modern large-scale translation and pre-trained language models such as BERT, GPT, mBART, and NLLB.

Modern Multilingual & Self-Supervised MT (2018 → Today)

Pretrained multilingual models (mBART, mT5, NLLB-200) handle 100+ languages. Enabled zero-shot and few-shot translation. Shifted the field toward self-supervised learning and massive pretraining on both parallel and monolingual data.

Summary

Translation has evolved from hand-crafted rules → statistical co-occurrence → neural encoder–decoder → attention → Transformer → multilingual pretraining. Each step reduced reliance on manual design, improved fluency and context handling, and scaled toward today’s large, general-purpose language models that translate with near-human quality.

Machine Translation Techniques – Comparative Table

| Feature / Aspect | Rule-Based MT (RBMT) | Statistical MT (SMT) | Neural MT (NMT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Hand-coded linguistic rules and bilingual dictionaries | Probabilistic models trained on parallel corpora | Deep learning with encoder-decoder neural architectures |

| Data Dependency | Low (relies more on expert linguistic knowledge) | High (requires large aligned corpora) | Very High (massive parallel corpora + monolingual corpora for fine-tuning, esp. in Transformer-based NMT) |

| Context Handling | Poor (translates word-by-word or phrase-by-phrase) | Limited (n-gram context, typically up to 5-grams) | Strong (full-sentence or even document-level context with attention mechanisms) |

| Fluency of Output | Low to Medium (grammar-focused but often unnatural) | Medium (statistical alignment may yield awkward phrasing) | High (natural and human-like outputs, better semantic coherence) |

| Linguistic Generalization | High (rule sets can apply across domains, assuming good design) | Poor (heavily corpus-dependent) | Medium to High (good generalization when pre-trained on large multilingual corpora) |

| Handling Rare Words / OOV Terms | Poor unless explicitly covered in rules or dictionaries | Poor unless seen in training data | Improved with subword units (e.g., Byte-Pair Encoding) |

| Support for Morphologically Rich Languages | Strong (can encode morphological rules explicitly) | Weak (suffers in morphologically complex languages) | Medium to Strong (improves with morph-aware tokenization and pretraining) |

| Interpretability | High (transparent rules) | Medium (alignments are partially interpretable) | Low (black-box nature of deep models) |

| Customization and Domain Adaptability | High (domain rules can be handcrafted) | Medium (requires domain-specific corpora) | High (via transfer learning, fine-tuning, prompt engineering) |

| Computational Cost | Low to Medium (CPU-friendly) | Medium (depends on data volume and alignment processing) | High (GPU-accelerated training and inference) |

| Real-Time Translation Capability | Feasible with limited vocabulary and rules | Feasible, but limited by decoding speed | Now feasible with optimized architectures (e.g., Transformers, quantization, beam search tricks) |

| Examples | Systran, Apertium | Moses (open-source SMT toolkit), IBM Model Series | Google Translate (post-2016), DeepL, OpenNMT, Facebook Fairseq, MarianNMT |

| Model Size | Small (depends on rule complexity) | Medium (phrase tables can be large) | Large to Very Large (e.g., GPT-4, mBART, mT5, NLLB, LLaMa models with billions of parameters) |

| Training Requirements | No training (hand-coded) | Requires word/phrase alignment, corpus cleaning, language modeling | Requires parallel corpora, GPUs/TPUs, potentially days of training |

| Recent Advances | Mostly static/legacy | Superseded by NMT | Transformer-based models, multilingual NMT, zero-shot translation, and massively multilingual pretraining |

| Main Academic Limitation | Lack of scalability and language coverage | Limited context window, phrase alignment errors | Lack of interpretability, high training cost, data bias risks |

Modern NLP Perspectives & Notes

- Transformer NMT (T-NMT) – Replaces older RNN/LSTM NMT models. Uses self-attention for parallel processing and better long-range dependency modeling. Dominant post-2017.

Papers: “Attention is All You Need” (Vaswani et al., 2017) - Pretrained Multilingual NMT – Models like mBART, mT5, NLLB-200 trained on 100+ languages.

Key ideas: Cross-lingual transfer, zero-shot translation.

Meta's NLLB project shows SOTA results on low-resource languages. - Subword Tokenization – Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), SentencePiece allow for better handling of unknown/morphologically complex words (major NMT advantage over SMT).

- Evaluation Metrics – BLEU remains common, but newer metrics (COMET, BERTScore, BLEURT) offer more semantically-aware assessment of NMT outputs.

Academic References (Core Papers & Toolkits)

- SMT: Philipp Koehn, Statistical Machine Translation, Cambridge Press (2009)

- Moses Toolkit: Koehn et al., 2007

- NMT Original Paper: Sutskever et al., “Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks”, 2014

- Attention Mechanism: Bahdanau et al., “Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate”, 2015

- Transformers: Vaswani et al., “Attention is All You Need”, 2017

- Multilingual MT (mBART): Liu et al., 2020

- NLLB-200 (Meta AI): “No Language Left Behind”, 2022

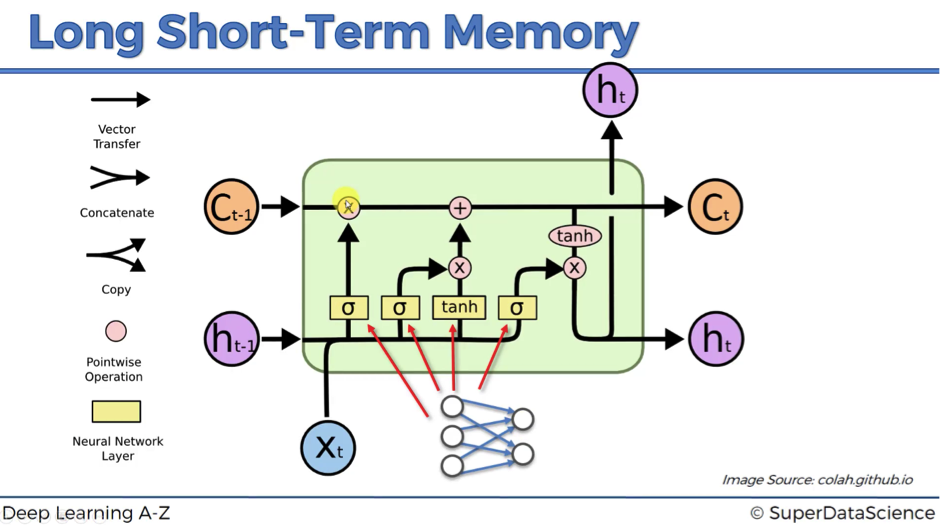

Long Short-Term Memory (Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997)

Abstract

The paper introduces Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), a novel recurrent neural network architecture designed to overcome the vanishing and exploding gradient problems in training RNNs. LSTM enforces constant error flow through Constant Error Carrousels (CECs), regulated by multiplicative input and output gates. This design enables learning dependencies spanning more than 1000 time steps. Experiments show that LSTM significantly outperforms Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT), Real-Time Recurrent Learning (RTRL), and other recurrent methods on long time-lag sequence tasks.

Problems Addressed

- Vanishing gradients: error signals decay exponentially, preventing long-term credit assignment.

- Exploding gradients: error signals grow uncontrollably, destabilizing training.

- Conflicting updates: naive constant error flow units suffered from contradictory weight signals.

- Prior methods (BPTT, RTRL, Elman nets, RCC, chunkers) failed on long time-lag problems (>100 steps).

Proposed Solution

- Constant Error Carrousel (CEC): linear self-connected units (weight = 1.0) preserve error indefinitely.

- Input and Output Gates: multiplicative gates control when information is written/read from memory.

- Memory Cells & Blocks: encapsulating CECs and gates to form scalable recurrent building blocks.

- Truncated error flow: gradient flows indefinitely inside cells, but truncates on exit for stability.

- Bias & construction strategies: prevent “abuse” or over-reliance on memory units.

Purpose

- Create an RNN architecture capable of learning long-term dependencies over thousands of time steps.

- Demonstrate feasibility of stable gradient-based training in recurrent systems.

- Solve benchmark sequence tasks unsolvable by previous algorithms.

Methodology

- Architecture: input → hidden layer of memory cells with gates → output. Fully recurrent hidden layer.

- Training: online learning, logistic sigmoid activations (specific ranges for g, h, and gates), truncated BPTT.

- Complexity: O(W) per time step (same as BPTT, more efficient than RTRL).

- Experiments:

- Embedded Reber Grammar recognition.

- Noisy/clean sequence tasks with lags up to 1000 steps.

- Bengio’s 2-sequence classification with noise.

- Continuous-value problems: Adding and Multiplication tasks.

- Sequence order tasks.

Results

- Reber Grammar: LSTM succeeded, unlike RTRL, Elman nets, or RCC.

- Long-lag tasks: Learned dependencies over 1000+ steps; BPTT/RTRL failed beyond ~10.

- Noise robustness: Handled noisy signals where others collapsed.

- Adding/Multiplication: Learned precise continuous-value storage & computation.

- Scaling: Training time grew slowly with sequence length (no exponential blow-up).

Conclusions

- LSTM eliminates vanishing gradients via constant error flow and gated memory.

- It solved tasks no other recurrent algorithm could handle at the time.

- Output gates proved crucial to separate long-term memory from short-term noise.

- Generalized well to noisy, real-valued, and distributed input sequences.

- Remaining limitation: potential “abuse” of memory cells, addressed via bias strategies.

Philosophical Impact

This paper marked a foundational breakthrough in sequence learning. By introducing explicit gated memory, Hochreiter & Schmidhuber transformed RNNs from unstable tools into powerful temporal models. LSTM became the basis for advances in speech recognition, language modeling, and deep learning architectures that dominate modern NLP and AI.

Featured Paper: LSTM (1997)

“By stabilizing error flow with memory cells and gates, LSTM solved the long-term dependency problem that crippled earlier RNNs — reshaping the future of deep learning.”

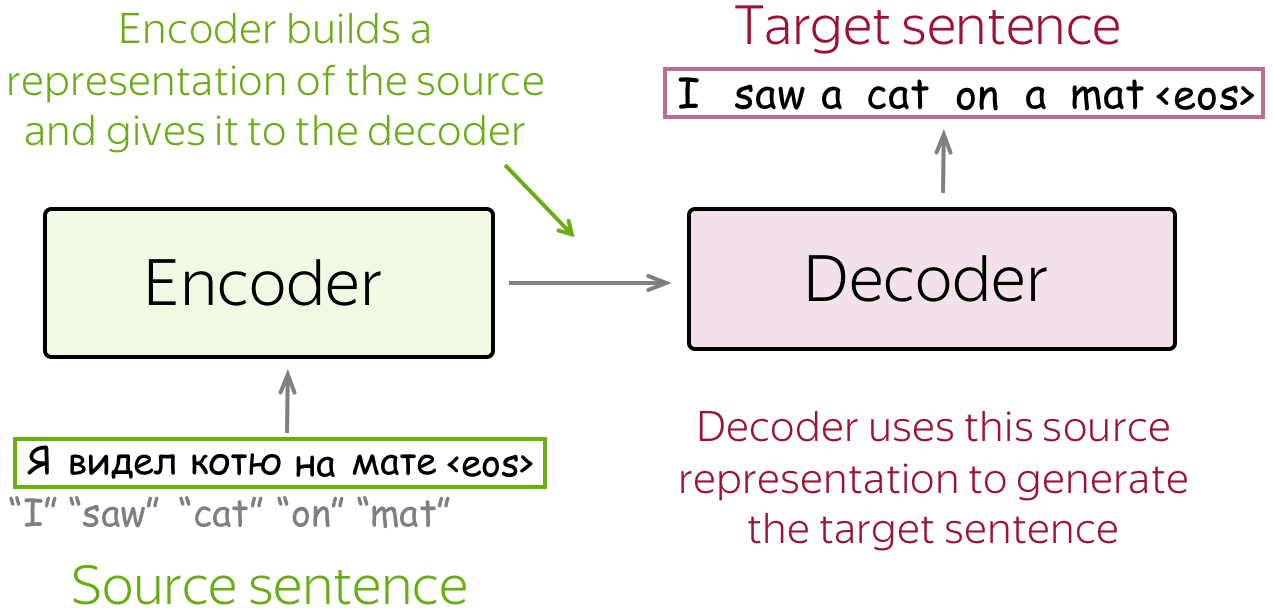

Learning Phrase Representations using RNN Encoder–Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation (Cho et al., 2014)

Abstract

This paper introduces a novel RNN Encoder–Decoder architecture for sequence-to-sequence learning, applied within statistical machine translation (SMT). The model consists of two recurrent neural networks: an encoder that maps a variable-length source phrase into a fixed-length vector, and a decoder that generates a target phrase conditioned on this vector. The model is trained to maximize the conditional probability of a target sequence given a source sequence. Empirical results show that using RNN Encoder–Decoder scores as additional features in phrase-based SMT improves translation performance. Furthermore, the model learns semantically and syntactically meaningful representations of phrases

Problems Addressed

- Phrase-based SMT relies heavily on co-occurrence statistics, which often fail for rare or unseen phrases.

- Traditional neural approaches (e.g., feedforward nets) require fixed-size inputs and outputs, making them unsuitable for variable-length sequences.

- Existing SMT translation models cannot effectively capture linguistic regularities or exploit sequence order beyond surface frequency counts

Proposed Solution

- Introduce the RNN Encoder–Decoder:

- Encoder RNN compresses a variable-length input sequence into a fixed-length vector.

- Decoder RNN generates the target sequence conditioned on this vector.

- Propose a novel hidden unit with reset and update gates (a precursor to GRU), enabling adaptive remembering and forgetting of context information.

- Use the RNN Encoder–Decoder to score phrase pairs in SMT phrase tables, integrating these scores into the log-linear model of a standard SMT system

Purpose

- To improve phrase-based SMT by providing better probability estimates for phrase pairs.

- To show that RNN-based models can learn continuous-space representations of phrases that encode both semantic and syntactic properties.

- To demonstrate that neural sequence models can generalize beyond frequency statistics and yield better translation performance

Methodology

- Architecture

- Encoder RNN reads source sequence → final hidden state represents source phrase.

- Decoder RNN generates target sequence, conditioned on encoder vector and previously generated tokens.

- Training objective: maximize log-likelihood of target sequences given sources.

- Experiments

- Task: English–French translation (WMT’14 dataset).

- Baseline: Moses phrase-based SMT system (BLEU 33.3).

- Enhancements tested:

- Baseline + RNN Encoder–Decoder.

- Baseline + Neural Language Model (CSLM).

- Combined Baseline + CSLM + RNN Encoder–Decoder.

- Training

- Vocabulary limited to 15k most frequent words.

- Model trained with Adadelta optimization.

- Embeddings visualized with Barnes-Hut-SNE for qualitative evaluation

Results

- BLEU score improvements:

- Baseline SMT: 33.30

- RNN Encoder–Decoder: 33.87

- CSLM + RNN: 34.64 (best)

- Qualitative analysis shows RNN Encoder–Decoder captures better linguistic regularities, especially for long or rare phrases, compared to SMT probabilities.

- Learned embeddings for words and phrases cluster semantically and syntactically similar items together

Conclusions

- The RNN Encoder–Decoder successfully learns meaningful phrase representations, improving SMT performance.

- It complements existing neural models (e.g., CSLM), with improvements being orthogonal rather than redundant.

- The proposed architecture shows strong potential beyond SMT, as a general method for learning sequence-to-sequence mappings.

- Future directions include replacing phrase tables entirely with neural models and extending applications to speech and other sequence tasks

Philosophical Impact

This work marked a paradigm shift in machine translation: proving that phrase representations need not be hand-crafted or solely frequency-based. By showing that neural sequence models can learn continuous-space semantic and syntactic representations, it opened the way for modern NMT and attention-based architectures that followed.

Featured Paper: RNN Encoder–Decoder (2014)

“This paper introduced the RNN Encoder–Decoder architecture, with reset and update gates, capable of learning phrase-level semantics and syntax. It demonstrated how neural models could complement and improve phrase-based SMT, laying the groundwork for end-to-end NMT.”

Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks (Sutskever, Vinyals, Le, 2014)

Abstract

The paper introduces an end-to-end framework for sequence-to-sequence learning using deep Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. The approach employs one LSTM to encode an input sequence into a fixed-length vector, and another LSTM to decode it into an output sequence. Evaluated on the WMT’14 English–French translation task, the model achieves a BLEU score of 34.8, surpassing a strong phrase-based SMT baseline (33.3). Further, rescoring SMT n-best lists yields 36.5 BLEU, close to the best published system at the time. Notably, the method works well on long sentences, aided by the novel trick of reversing input sequences, which eases optimization and improves performance

Problems Addressed

- Standard deep neural networks require fixed-dimensional inputs and outputs, making them unsuitable for variable-length sequence tasks such as translation, speech recognition, or question answering.

- Existing SMT systems rely on statistical alignment and phrase tables, but cannot fully leverage deep learning’s representational power.

- Training recurrent models for sequence-to-sequence mapping faces challenges due to long-term dependencies and optimization difficulties

Proposed Solutions

- Use a two-stage LSTM model:

- Encoder LSTM: reads the input sequence and produces a fixed-length vector.

- Decoder LSTM: generates the output sequence conditioned on this vector.

- Employ deep LSTMs (4 layers, 1000 units each) to improve capacity.

- Introduce a simple yet powerful trick: reverse the words in the source sentence during training. This creates short-term dependencies between source and target words, reducing optimization difficulty and significantly improving BLEU scores

Purpose

- To demonstrate that large LSTMs can serve as a general solution for sequence-to-sequence learning, making minimal assumptions about input/output structures.

- To show that neural networks can outperform phrase-based SMT baselines on large-scale machine translation tasks.

- To establish a foundation for end-to-end neural sequence learning applicable to translation and beyond

Methodology

- Data: WMT’14 English–French dataset (12M sentence pairs).

- Model:

- Two separate LSTMs (encoder + decoder).

- 160k source vocabulary, 80k target vocabulary; out-of-vocabulary mapped to UNK.

- Ensemble of 5 LSTMs (384M parameters).

- Training:

- Stochastic Gradient Descent with gradient clipping.

- Batching by sentence length to reduce wasted computation.

- Parallelized across 8 GPUs.

- Decoding: Left-to-right beam search (beam size 1–12).

- Evaluation: BLEU scores on test set, comparisons to SMT baseline, analysis of long sentence performance and learned representations

Results

- Direct translation:

- Ensemble of 5 reversed LSTMs → 34.81 BLEU, outperforming SMT baseline (33.30).

- Rescoring SMT n-best lists:

- Single LSTM → 35.6–35.8 BLEU.

- Ensemble of 5 reversed LSTMs → 36.5 BLEU, close to SOTA (37.0).

- Qualitative analysis:

- Learned representations capture word order and are robust to syntactic alternations (active vs. passive).

- Performance on long sentences remained strong, contradicting earlier concerns about memory bottlenecks.

- Key insight: reversing source sentences improved perplexity (5.8 → 4.7) and BLEU (25.9 → 30.6 for single models)

Conclusions

- A simple encoder–decoder LSTM framework can achieve competitive or superior results in large-scale machine translation.

- The reversal trick provides a crucial optimization advantage, highlighting the importance of data preprocessing for sequence learning.

- Neural networks can successfully replace phrase-based SMT by learning direct sequence mappings.

- The work establishes a general paradigm for end-to-end sequence-to-sequence learning, paving the way for subsequent advancements such as attention and Transformers

Philosophical Impact

This paper embodied a leap in thinking: translation and sequence learning could be modeled end-to-end without explicit alignment tables or hand-engineered rules. By introducing a two-stage encoder–decoder with LSTMs, it proved that deep learning could map variable-length sequences directly. The simple yet radical idea of reversing input sentences highlighted how data representation choices affect optimization. Its success paved the way for attention mechanisms and Transformers, redefining the paradigm of sequence transduction.

Featured Paper: Seq2Seq with LSTMs (2014)

“This work showed that deep LSTMs could learn to translate entire sentences directly, outperforming phrase-based SMT baselines and inspiring the attention revolution.”

Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate (Bahdanau, Cho, Bengio, 2015)

Abstract

The paper proposes an improved neural machine translation (NMT) model that simultaneously learns to align and translate. Unlike earlier encoder–decoder frameworks that compress a source sentence into a single fixed-length vector, the proposed model introduces an attention mechanism allowing the decoder to selectively focus on relevant parts of the source sentence while generating each target word. This approach improves performance on English–French translation, reaching results comparable to state-of-the-art phrase-based SMT, and yields interpretable soft-alignments between source and target tokens

Problems Addressed

- Fixed-length bottleneck: Prior encoder–decoder models required encoding an entire source sentence into one vector, which caused severe performance degradation on long sentences.

- Lack of alignment modeling: Earlier NMT systems had no explicit mechanism to capture word-to-word or phrase-to-phrase correspondences, unlike phrase-based SMT.

- Scalability: Need for a neural architecture that could handle long sequences while maintaining translation quality

Proposed Solutions

- Introduce a soft attention mechanism: For each target word, the model computes a context vector as a weighted sum of source annotations, where weights represent soft alignment probabilities.

- Use a bidirectional RNN encoder to generate annotations for each source word, capturing both left and right contexts.

- Jointly train encoder, decoder, and alignment model end-to-end via maximum likelihood estimation.

- Replace the fixed-vector bottleneck with adaptive context vectors, enabling the decoder to dynamically retrieve relevant information from the source sentence

Purpose

- To overcome the limitations of fixed-length sentence representations in NMT.

- To demonstrate that neural attention mechanisms improve both translation quality and interpretability.

- To provide a unified framework where alignment and translation are jointly optimized, reducing reliance on external SMT components

Methodology

- Architecture

- Encoder: Bidirectional RNN generates a sequence of hidden states (annotations).

- Attention mechanism: Computes alignment scores between decoder state and encoder annotations, normalizing them into weights.

- Decoder: Conditioned on previous outputs, hidden state, and attention-derived context vector.

- Dataset

- English–French WMT’14 parallel corpus (~348M words).

- Shortlist vocabularies of 30k most frequent words for both source and target.

- Models compared

- Baseline: RNN encoder–decoder without attention (RNNencdec).

- Proposed: Attention-based NMT (RNNsearch).

- Training

- Optimization: Mini-batch SGD with Adadelta, gradient clipping.

- Trained on GPUs (NVIDIA TITAN/Quadro).

- Evaluation: BLEU scores and qualitative alignment visualizations

Results

- Quantitative:

- RNNsearch consistently outperforms RNNencdec across sentence lengths.

- BLEU scores:

- RNNencdec-50: 17.82

- RNNsearch-50: 26.75 (34.16 on sentences without UNK)

- Extended training (RNNsearch-50?): 28.45 (36.15 without UNK), matching phrase-based SMT (Moses: 33.30 / 35.63)

- Qualitative:

- Learned alignments are linguistically meaningful and often monotonic, but capable of non-trivial reorderings (e.g., adjective–noun swaps).

- Soft alignments handle ambiguous cases (e.g., article gender in French) better than hard alignments.

- Demonstrated robustness on long sentences, where baseline models failed

Conclusions

- The proposed attention-based encoder–decoder overcomes the fixed-length bottleneck of early NMT models.

- The model achieves translation performance comparable to state-of-the-art SMT while providing interpretable alignments.

- Attention allows the model to handle long sequences and linguistic reordering naturally.

- This work established attention as a foundational principle in NMT and deep learning, directly inspiring subsequent architectures like the Transformer

Philosophical Impact

This paper redefined the landscape of machine translation by introducing attention—a mechanism that allowed neural networks to focus on relevant parts of the source sentence during decoding. Instead of forcing information into a single fixed-length vector, it enabled dynamic context retrieval, making translation of long and complex sentences feasible. Philosophically, it shifted NMT from compression to selective focus, inspiring not only subsequent attention variants but also the Transformer revolution.

Featured Paper: Attention in NMT (2015)

“This work overcame the fixed-length bottleneck of early NMT models by learning soft alignments, enabling dynamic focus on source words and laying the foundation for modern attention architectures.”

On Using Very Large Target Vocabulary for Neural Machine Translation (Jean, Cho, Memisevic, Bengio, 2015)

Abstract

The paper addresses the vocabulary limitation in Neural Machine Translation (NMT), where training and decoding complexity grows with target vocabulary size. The authors propose an importance sampling–based algorithm that enables training with very large vocabularies efficiently, and introduce candidate lists for efficient decoding. Empirical results on WMT’14 English→French and English→German show that large-vocabulary NMT matches or outperforms shortlist-based models and achieves near state-of-the-art BLEU scores.

Problems Addressed

- Standard NMT requires limiting target vocabularies (30k–80k), replacing rare words with [UNK].

- Performance degrades heavily when translations require many out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words.

- Computational cost of softmax normalization grows linearly with vocabulary size.

- Conventional fixes (hierarchical softmax, class-based models, noise-contrastive estimation) reduce training complexity but not decoding complexity.

Proposed Solution

- Approximate training with importance sampling: Train using only a sampled subset of the vocabulary per update, reducing normalization cost.

- Partition-based vocabulary subsets: Divide training corpus, define per-partition vocabularies to fit GPU memory.

- Candidate lists in decoding: Use dictionaries and unigram statistics to restrict possible target words at test time.

- UNK replacement strategy: Replace [UNK] tokens using word alignments or bilingual dictionaries.

Purpose

- Enable very large target vocabularies in NMT without prohibitive computational cost.

- Improve translation accuracy, especially for rare words.

- Match or surpass state-of-the-art SMT and NMT systems.

Methodology

- Datasets

- English→French: 12M sentences (Europarl, Common Crawl, UN, News Commentary, Gigaword).

- English→German: Europarl, Common Crawl, News Commentary.

- Models

- Baseline: RNNsearch with attention (Bahdanau et al., 2014) with 30k vocab (English–French), 50k vocab (English–German).

- Proposed Models (RNNsearch-LV): 500k vocabularies trained via importance sampling.

- Training details

- Beam search (beam=12), dropout, gradient clipping.

- Candidate lists with K=15k–50k for decoding.

- Bilingual dictionary for UNK replacement.

- Evaluation

- BLEU scores on WMT’14 test set.

- Development on news-test 2012/2013.

Results

- English→French:

- Baseline RNNsearch: 29.97 BLEU.

- RNNsearch-LV: 32.68 BLEU.

- + UNK replacement: 34.11 BLEU.

- Ensemble: 37.19 BLEU (near SOTA).

- English→German:

- Baseline: 16.46 BLEU.

- RNNsearch-LV: 16.95 BLEU.

- + UNK replacement: 18.89 BLEU.

- Ensemble: 21.59 BLEU (better than previous SOTA of 20.67).

- Decoding speed: Candidate lists brought decoding time close to baseline despite larger vocabularies.

Conclusions

- Large-vocabulary NMT trained with importance sampling outperforms shortlist-based models.

- Candidate lists enable practical decoding speeds.

- UNK replacement and ensembles further boost performance.

- The approach achieves near state-of-the-art on WMT’14 benchmarks and surpasses phrase-based SMT.

Philosophical Impact

This work demonstrated that NMT need not be constrained by artificial vocabulary limits. By making large-vocabulary models practical, it paved the way for handling rare words more effectively and influenced later architectures where scaling vocabulary size became standard (e.g., subword methods like BPE and eventually large-scale Transformers).

Featured Paper: Large Vocabulary NMT (2015)

“This work removed the vocabulary bottleneck in NMT, showing that large-scale vocabularies could be both trainable and decodable, paving the way for modern subword and large-scale Transformer approaches.”

Effective Approaches to Attention-based Neural Machine Translation (Luong, Pham, Manning, 2015)

Abstract

This paper systematically explores and evaluates architectural variants of attention mechanisms in neural machine translation (NMT). The authors propose two key models: global attention, where the decoder attends to all source words, and local attention, where the decoder selectively attends to a subset of source words. Additionally, they introduce an input-feeding approach to incorporate past alignment decisions. Experiments on English–German WMT tasks show that these attention models improve translation quality by up to +5.0 BLEU over non-attentional baselines and establish new state-of-the-art results (25.9 BLEU) in WMT’15 English→German

Problems Addressed

- Previous NMT attention models (Bahdanau et al., 2015) lacked exploration of alternative architectures.

- Global attention requires attending to all source positions at every decoding step, which is computationally expensive.

- Existing models did not effectively capture coverage of alignments across translation steps, leading to over- or under-translation.

- Unclear which alignment functions (dot, general, concat, location) work best for NMT

Proposed Solutions

- Global Attention – attends to all source positions when predicting each target word.

- Local Attention – focuses only on a small window around a predicted source position:

- local-m: assumes monotonic alignments.

- local-p: predicts alignment positions dynamically via a learned function, combined with Gaussian weighting.

- Input-feeding approach – feeds attentional context vectors into subsequent decoding steps to inform future alignment decisions.

- Systematic comparison of alignment functions (dot, general, concat, location) to identify optimal scoring methods

Purpose

- To investigate how different attention architectures affect NMT performance.

- To improve efficiency, accuracy, and alignment quality in NMT systems.

- To move beyond the single Bahdanau-style attention model and establish design principles for future NMT attention mechanisms

Methodology

- Datasets:

- WMT’14 English–German (4.5M sentence pairs, 116M English, 110M German words).

- Vocabulary limited to top 50k most frequent words.

- Architecture:

- 4-layer stacked LSTMs with 1000 hidden units each.

- Embedding size: 1000.

- Trained with SGD, dropout (p=0.2), gradient clipping, reversed source sentences.

- Evaluation:

- Tokenized BLEU (comparable with NMT work).

- NIST BLEU (for WMT official results).

- Also evaluated alignment quality with Alignment Error Rate (AER).

- Comparisons:

- Against phrase-based SMT baselines.

- Against Bahdanau et al. (2015) and Jean et al. (2015) attention models

Results

- English→German (WMT’14):

- Base model (reverse + dropout): BLEU 14.0.

- Global attention: BLEU 16.8 (+2.8).

- Input-feeding: BLEU 18.1 (+1.3).

- Local-p attention: BLEU 19.0 (+0.9).

- Unknown replacement: BLEU 20.9 (+1.9).

- Ensemble (8 models): BLEU 23.0 (SOTA at the time).

- English→German (WMT’15):

- Ensemble + unknown replacement: BLEU 25.9, surpassing prior SOTA (24.9).

- German→English (WMT’15):

- Base (reverse): BLEU 16.9.

- Best model (global dot + dropout + feed + unk): BLEU 24.9, approaching SOTA (29.2).

- Qualitative:

- Attention improved translation of rare words and proper names.

- Better performance on long sentences, addressing a major weakness of non-attentional NMT.

- Alignment Error Rates (AER): local attention (0.34–0.36) comparable to Berkeley Aligner (0.32)

Conclusions

- Both global and local attention mechanisms substantially improve NMT, with local predictive attention offering efficiency and interpretability advantages.

- The input-feeding approach enhances coverage, preventing repetition or omission in translation.

- Different alignment scoring functions yield different strengths: dot works best for global models, general for local models.

- Attention-based NMT systems not only outperform earlier non-attentional baselines but also rival and surpass traditional SMT.

- This work established a systematic framework for attention in NMT, laying the groundwork for later developments such as multi-head attention in Transformers

Philosophical Impact

This paper marked a turning point: it transformed attention from a single experimental idea (Bahdanau et al., 2015) into a systematic framework for neural translation. By introducing global and local attention, and the input-feeding mechanism, it crystallized design principles that shaped all later models. Its careful analysis proved that attention was not just a hack but a foundational paradigm—paving the road directly to multi-head attention and Transformers.

Featured Paper: Attention Variants in NMT (2015)

“By analyzing global and local attention models, this work showed how different attentional mechanisms improve translation, setting the stage for the evolution of modern sequence architectures.”

Long Short-Term Memory-Networks for Machine Reading (Cheng, Dong, Lapata, 2016)

Abstract

The paper introduces a machine reading simulator—a neural model that processes text incrementally while leveraging memory networks and attention to enhance reasoning over sequences. By replacing the standard LSTM’s single memory cell with a memory tape and embedding intra-attention, the model (LSTMN) learns to induce token-level relations and store richer contextual information. Experiments in language modeling, sentiment analysis, and natural language inference demonstrate that the approach matches or outperforms state-of-the-art baselines.

Problems

- Vanishing/exploding gradients in RNN training, limiting long-sequence learning.

- Memory compression: standard LSTMs collapse long sequences into a single vector, hindering generalization.

- Lack of structural bias: sequence models ignore latent syntactic/semantic relations among tokens.

Proposed Solutions

- Introduce Long Short-Term Memory-Networks (LSTMN):

- Replace single LSTM memory cell with a growing memory tape.

- Add an intra-attention mechanism to selectively retrieve relations between tokens.

- Store contextual representations without recursive compression.

- Extend the framework to encoder–decoder architectures with shallow and deep attention fusion for sequence-to-sequence tasks.

Purposes

- To design a neural machine reader capable of simulating human-like incremental text comprehension.

- To enable recurrent models to memorize longer sequences effectively and induce lexical relations.

- To provide a general-purpose reading simulator adaptable across multiple NLP tasks.

Methodology

- Model architecture:

- Extend LSTM with a memory tape and intra-attention addressing.

- Each token is linked with adaptive memory slots.

- Attention computes weighted relations among past tokens.

- Fusion with Seq2Seq:

- Shallow fusion: LSTMN replaces LSTM in encoder/decoder.

- Deep fusion: combines intra- and inter-attention for richer alignments.

- Experiments:

- Language modeling on Penn Treebank (perplexity evaluation).

- Sentiment analysis on Stanford Sentiment Treebank.

- Natural language inference on SNLI corpus.

Results

- Language Modeling:

- Single-layer LSTMN achieves perplexity 108, outperforming standard LSTM (115).

- Deep LSTMN further improves (perplexity 102).

- Sentiment Analysis:

- Competitive with state-of-the-art CNN and tree-based models; 2-layer LSTMN achieves 87.0% binary accuracy.

- Natural Language Inference:

- Deep fusion LSTMN reaches 86.3% accuracy, surpassing previous LSTM-based approaches (e.g., mLSTM 86.1%).

Conclusions

- LSTMN effectively overcomes limitations of traditional LSTMs by explicit memory representation and intra-attention reasoning.

- Demonstrates consistent improvements across language modeling, sentiment analysis, and NLI.

- Contributions extend beyond LSTMs, offering a general blueprint for integrating structured memory and attention in recurrent models.

- Future work: extending to nested structure reasoning and applying to tasks requiring explicit compositionality and dependency modeling.

Philosophical Impact

This work challenged the limits of recurrent sequence models by embedding explicit memory structures and intra-attention inside LSTMs. Instead of collapsing an entire sequence into a single vector, LSTMN preserved a growing memory tape, simulating how humans fixate and recall tokens incrementally. Philosophically, it signaled a shift from viewing RNNs as pure compressors to viewing them as reasoning readers, capable of modeling latent relations across words. It bridged the gap between memory networks and LSTMs, paving the way for more structured and interpretable neural reading systems.

Featured Paper: LSTMN (2016)

“The LSTMN learns to induce token-level relations and stores contextual representations without collapsing them, offering a general-purpose machine reading simulator that outperforms standard LSTMs.”

Attention Is All You Need (Vaswani et al., 2017)

Abstract

The paper introduces the Transformer, a novel neural sequence transduction model that relies entirely on attention mechanisms, dispensing with recurrence and convolution. The Transformer achieves superior translation quality, faster training, and greater parallelizability compared to RNN- and CNN-based models. On WMT’14 English–German, the Transformer obtains 28.4 BLEU, surpassing previous best results by over +2 BLEU. On WMT’14 English–French, it sets a new single-model state-of-the-art with 41.8 BLEU while training in just 3.5 days on 8 GPUs. The architecture also generalizes well to tasks beyond translation, such as English constituency parsing

️ Problems Addressed

- Sequential bottleneck of RNNs: Recurrent models process tokens step by step, hindering parallelism and slowing training.

- Difficulty modeling long-range dependencies: RNNs and CNNs require many steps to connect distant tokens.

- Computational inefficiency: Convolutions and recurrences increase training costs, limiting scalability.

- Limited interpretability: Previous models lacked mechanisms to clearly expose syntactic and semantic dependencies

Proposed Solutions

- Develop the Transformer, built entirely on self-attention and feed-forward layers.

- Replace recurrence with scaled dot-product attention and multi-head attention, enabling direct modeling of global dependencies.

- Introduce positional encodings (sinusoidal functions) to capture order information in sequences.

- Employ residual connections, layer normalization, and dropout for stable training.

- Optimize training with the Adam optimizer and a novel learning rate schedule (warmup + inverse square root decay)

Purposes

- To eliminate the computational constraints of RNN/CNN sequence models.

- To demonstrate that attention-only architectures can outperform state-of-the-art machine translation systems.

- To provide a scalable, interpretable framework applicable beyond translation (e.g., parsing, multimodal tasks).

Methodology

- Architecture:

- Encoder: 6 layers of self-attention + feed-forward networks.

- Decoder: 6 layers, with masked self-attention and encoder–decoder attention.

- Hidden dimension: 512; feed-forward dimension: 2048; 8 attention heads.

- Big model: larger hidden (1024), feed-forward (4096), and 16 heads.

- Training:

- Data: WMT’14 English–German (4.5M pairs, 37k BPE tokens); English–French (36M pairs, 32k tokens).

- Hardware: 8 NVIDIA P100 GPUs.

- Training time: 12 hours (base), 3.5 days (big).

- Evaluation:

- BLEU for translation.

- English constituency parsing (WSJ).

- Ablation studies on attention heads, dimensions, dropout, and positional encoding

Results

- English→German:

- Transformer (base): 27.3 BLEU.

- Transformer (big): 28.4 BLEU, +2 BLEU over prior best ensembles.

- English→French:

- Transformer (big): 41.8 BLEU, new single-model SOTA, at <25% training cost of GNMT.

- Parsing:

- Transformer achieves 91.3 F1 (WSJ-only), competitive with RNN grammar models.

- Semi-supervised setting: 92.7 F1, surpassing prior baselines.

- Ablations:

- Multi-head attention improves BLEU by up to +0.9 over single-head.

- Larger models consistently outperform smaller ones.

- Sinusoidal vs learned positional encoding: nearly identical performance

Conclusions

- The Transformer introduces a paradigm shift: attention alone is sufficient for sequence modeling.

- It achieves state-of-the-art performance in translation and parsing at a fraction of the training cost.

- The architecture improves parallelization, efficiency, and interpretability compared to RNN/CNN models.

- This work laid the foundation for subsequent advances in large-scale pretraining (e.g., BERT, GPT) and multimodal transformers.

- Future directions include applying restricted/local attention for very long sequences and extending to other modalities (speech, images, video)

Philosophical Impact

This paper marked a paradigm shift: it argued that attention alone is enough to model sequence transduction. By discarding recurrence and convolution entirely, the Transformer proved that language understanding could be achieved through parallelizable global interactions between tokens. Its clean architecture not only accelerated training but also improved interpretability, laying the foundation for today’s large-scale pretrained models such as BERT and GPT.

Featured Paper: Transformer (2017)

“The Transformer dispensed with recurrence and convolution, relying entirely on multi-head self-attention. It achieved state-of-the-art BLEU scores while being faster, more scalable, and more interpretable — a decisive moment in deep learning history.”

Google’s Neural Machine Translation System: Bridging the Gap Between Human and Machine Translation (Wu et al., 2016)

Abstract

This paper presents GNMT, Google’s large-scale Neural Machine Translation system designed to overcome critical shortcomings of earlier NMT models.

GNMT employs an 8-layer LSTM encoder–decoder architecture with residual connections and attention, combined with wordpiece modeling to handle rare words,

model/data parallelism for efficient training, and quantization-aware inference for production deployment.

GNMT achieves state-of-the-art performance on WMT’14 English–French and English–German benchmarks, and reduces translation errors by 60% compared to Google’s previous phrase-based system,

approaching human-level accuracy in side-by-side evaluations.

Problems Addressed

- Slow training and inference due to deep recurrent networks.

- Poor handling of rare or unseen words, leading to mistranslations.

- Incomplete translations where models fail to cover all input tokens.

- Difficulty scaling to production systems with large datasets and real-time demands.

Proposed Solutions

- Architecture: Deep stacked LSTMs (8 encoder + 8 decoder layers) with residual connections to stabilize training.

- Parallelism: Model parallelism across GPUs and residual-attention linking (bottom decoder → top encoder) for efficiency.

- Wordpiece Model (WPM): Subword units to balance flexibility of characters with efficiency of words, enabling robust rare-word translation.

- Beam Search Refinements: Length normalization and coverage penalty to ensure complete translations.

- Quantization-aware Inference: Low-precision arithmetic optimized for TPUs to accelerate decoding with minimal loss in quality.

- Reinforcement Learning Refinement: Fine-tuning models to directly optimize BLEU, though with limited impact on human judgment.

Purpose

- To develop a robust, accurate, and efficient NMT system suitable for real-world production (Google Translate).

- To close the gap between phrase-based SMT and neural methods, both in translation quality and deployment feasibility.

- To explore architectural, algorithmic, and systems-level innovations enabling scalability to massive datasets and multilingual use cases.

Methodology

- Architecture:

- 1 bi-directional + 7 uni-directional encoder LSTM layers, residual connections, attention mechanism.

- Datasets:

- WMT’14 English–French (36M sentence pairs), English–German (5M pairs).

- Google’s massive internal production datasets.

- Training:

- Optimizers: Adam (early stages) + SGD (later refinement).

- Gradient clipping, dropout, parallel training across ~96 GPUs.

- RL fine-tuning with GLEU (sentence-level reward).

- Inference:

- Quantized models on TPUs with batch beam search decoding.

- Evaluation:

- BLEU scores + human side-by-side ratings.

Results

- WMT’14 English–French:

- Best single model: 38.95 BLEU (WPM-32K).

- RL refinement: +1 BLEU (39.92).

- Ensemble of 8 models: 41.16 BLEU (SOTA at the time).

- WMT’14 English–German:

- Best single model: 24.61 BLEU (WPM-32K).

- Ensemble of 8 models: 26.30 BLEU.

- Production Data:

- 60% fewer translation errors vs. phrase-based MT.

- Human evaluations: GNMT outputs approach average human translator quality in some language pairs.

Conclusions

- GNMT demonstrates that deep LSTMs with attention, wordpiece modeling, and system-level optimizations can outperform phrase-based systems at scale.

- Wordpieces effectively solve rare-word translation and improve robustness across languages.

- Quantization and parallelism make large NMT models practical for real-time production.

- Although reinforcement learning fine-tuning boosts BLEU scores, it has limited effect on perceived translation quality.

- GNMT marks a turning point in practical neural MT, reducing the gap between human and machine translation.

Philosophical Impact

GNMT represented a watershed moment in the history of neural translation.

It was the first time a massive-scale neural system powered a global product like Google Translate,

proving that deep learning had matured beyond research demos and could serve billions of users daily.

By addressing practical bottlenecks — rare words, scaling across GPUs, efficient inference on TPUs,

and robust handling of long sentences — GNMT showed that neural MT was not just a theoretical curiosity

but an industrial reality.

GNMT’s use of wordpiece models solved the long-standing rare-word problem,

while its 8-layer residual LSTMs demonstrated that deep recurrent architectures could be trained and deployed at scale.

Its beam search refinements (length normalization and coverage penalties) highlighted how decoding strategies

mattered as much as model design.

Most importantly, GNMT closed much of the gap between human and machine translation,

reducing errors by 60% compared to phrase-based SMT and delivering output that, for some language pairs,

rivaled professional translators in human evaluations.

This paper was a philosophical turning point: it cemented the idea that neural networks could be engineered, optimized,

and scaled into production systems — paving the way for the Transformer revolution that followed.

Featured Paper: Google’s Neural Machine Translation System (2016)

“GNMT reduced translation errors by 60% compared to phrase-based SMT, introduced scalable architectures with attention and wordpiece modeling, and became the first neural system to power Google Translate — a decisive proof that neural MT was ready for global deployment.”

Google’s Multilingual Neural Machine Translation System (Johnson et al., 2017)

Abstract

This paper introduces a multilingual neural machine translation (NMT) approach that allows a single model to translate between multiple language pairs. By adding an artificial token specifying the target language, the system leverages a shared encoder–decoder with attention and a joint subword vocabulary. The model not only achieves competitive or superior results compared to bilingual systems but also demonstrates zero-shot translation — direct translation between language pairs unseen during training. Visualization of learned representations suggests the emergence of an interlingua-like structure.

Problems Addressed

- Traditional NMT requires separate models for each language pair, which is computationally inefficient at scale.

- Poor performance on low-resource language pairs due to limited parallel data.

- No mechanism for direct translation between language pairs lacking training data (e.g., Japanese→Korean).

- Scalability issues: 100 languages would naïvely require 10,000 bilingual models.

Proposed Solutions

- Target-Language Tokens: Add a token like

<2fr>to mark the target language. - Shared Architecture: One encoder–decoder–attention model across all languages.

- Wordpiece Model (32k vocab): Subword units to handle rare words and diverse scripts.

- Balanced Training: Oversampling low-resource pairs to prevent domination by high-resource pairs.

- Zero-Shot Translation: Translate between unseen language pairs using shared representations.

- Representation Analysis: t-SNE visualizations reveal clustering across languages.

Purpose

- Simplify large-scale translation with one multilingual model instead of many bilingual ones.

- Improve low-resource translation quality through parameter sharing.

- Enable zero-shot translation between unseen language pairs.

- Explore whether NMT learns a universal interlingua representation.

Methodology

- Architecture: GNMT-style 8-layer LSTMs with attention and residual connections.

- Datasets:

- WMT’14 English–French and English–German.

- Massive multilingual datasets from Google Translate production.

- Training: Mixed mini-batches, oversampling of low-resource languages.

- Evaluation: BLEU scores and human side-by-side ratings.

- Analysis: Projection of embeddings to test for interlingua structure.

Results

- WMT’14 Benchmarks: Multilingual model matches or surpasses strong bilingual baselines.

- Production Systems: One model reduces maintenance costs while maintaining quality.

- Zero-Shot Translation: Achieves non-trivial accuracy without direct training data.

- Representation Analysis: Cross-lingual clustering supports universal interlingua hypothesis.

Conclusions

- A single multilingual NMT model can replace thousands of bilingual models at scale.

- Target-language tokens and shared wordpiece vocabularies ensure robust performance.

- Multilingual training boosts low-resource translation and enables zero-shot learning.

- Evidence of a universal interlingua emerges in the model’s representations.

- This work paved the way for multilingual pretraining frameworks like mBERT, XLM-R, and mT5.

Philosophical Impact

The Multilingual NMT system marked a bold philosophical leap in how we think about translation.

Instead of building thousands of bilingual models for every language pair, Johnson et al. proposed

that a single universal model could learn to translate across many languages simultaneously.

By introducing target-language tokens and a shared wordpiece vocabulary, the paper showed that neural networks

could discover cross-lingual patterns and even achieve zero-shot translation — translating between language pairs

never explicitly seen during training.

This work introduced the idea of a learned interlingua within neural models, evidenced by t-SNE visualizations of

embeddings where semantically similar sentences clustered together regardless of language.

It redefined the philosophy of machine translation: from building systems for each pair to training one system

that speaks them all.

Beyond translation, this paper seeded the vision of multilingual pretraining, inspiring future advances like

mBERT, XLM-R, and mT5. It proved that NMT was not just about higher BLEU scores, but about enabling

a more universal, inclusive approach to language understanding in AI.

Featured Paper: Multilingual NMT (2017)

“This paper proved that a single NMT model can translate dozens of languages, achieve zero-shot translation, and even learn interlingual representations — a philosophical shift toward universal language models.”

Evolution of Machine Translation: Statistical → Neural Era

| Old Paradigm | New Paradigm | Paper / Breakthrough |

|---|---|---|

| Phrase Tables (frequency-based) | Learned phrase representations (RNN Encoder–Decoder) | Cho et al. 2014 |

| Fixed phrase probabilities | Continuous embeddings capturing syntax & semantics | Cho et al. 2014 |

| Fixed-length input compression | Variable-length encoding & decoding via LSTMs | Sutskever et al. 2014 (Seq2Seq) |

| Sequential bottleneck (one hidden state) | Reversal trick for optimization + deep stacked LSTMs | Sutskever et al. 2014 |

| One-to-one word mapping | Soft alignment between source & target tokens | Bahdanau et al. 2015 |

| Hard alignments (IBM models, SMT) | Differentiable attention mechanism | Bahdanau et al. 2015 |

| Global sentence compression | Global vs. Local attention strategies | Luong et al. 2015 |

| No tracking of past alignments | Input-feeding to incorporate history | Luong et al. 2015 |

| Memoryless RNNs | Memory tapes with intra-attention (token-to-token relations) | Cheng et al. 2016 (LSTMN) |

| Linear hidden state dependence | Structured relational reasoning inside recurrent models | Cheng et al. 2016 |

| Recurrent sequential computation | Self-attention (parallelizable, long-range deps) | Vaswani et al. 2017 (Transformer) |

| Order via recurrence | Positional encoding (sinusoidal) | Vaswani et al. 2017 |

| RNN/CNN encoders | Fully attention-based encoder–decoder | Vaswani et al. 2017 |

| Hand-crafted UNK handling | Wordpiece models for open vocabulary | Wu et al. 2016 (GNMT) |

| High-cost inference | Quantized inference on TPUs (production scale) | Wu et al. 2016 |

| BLEU-optimized post-processing | Reinforcement Learning fine-tuning with GLEU | Wu et al. 2016 |

| Separate bilingual models per pair | Single multilingual model with target-language tokens | Johnson et al. 2017 (Multilingual NMT) |

| No mechanism for unseen pairs | Zero-shot translation (emergent interlingua) | Johnson et al. 2017 |

| Pure supervised (X→Y) | Semi-supervised / self-supervised pretraining (attention generalization) | Post-Transformer Era |

Insights

- From statistical frequency tables → continuous phrase embeddings.

- From fixed-length bottlenecks → variable-length sequence modeling (Seq2Seq).

- From implicit alignment → explicit differentiable attention (Bahdanau, Luong).

- From sequential recurrence → parallelizable self-attention (Transformer).

- From SMT pipelines → production-scale NMT (GNMT).

- From bilingual-only → multilingual with zero-shot capabilities (Johnson et al., 2017).

- And finally, toward unsupervised/self-supervised paradigms with large pre-trained models.

Metrics & Performance Across MT Papers

| Paper | Metric(s) | Key Results | Improvement vs Prior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cho et al. 2014 – RNN Encoder–Decoder | BLEU (WMT’14 En–Fr) | Baseline SMT: 33.3 → +RNN Encoder–Decoder: 33.87 | Small BLEU gain; better rare/long phrase handling qualitatively |

| Sutskever et al. 2014 – Seq2Seq LSTM | BLEU (WMT’14 En–Fr) | Single LSTM: 30.6 → Ensemble (5): 34.8; +SMT rescoring: 36.5 | Surpassed strong SMT (33.3), robust on long sentences |

| Bahdanau et al. 2015 – Attention (RNNsearch) | BLEU (WMT’14 En–Fr) | RNNencdec weak on long sentences; RNNsearch-50: 28.45 (36.15 w/o UNKs) vs Moses SMT: 33.30 (35.63 w/o UNKs) | Comparable to SMT on long sentences, eliminated fixed-length bottleneck |

| Luong et al. 2015 – Global/Local Attention | BLEU (WMT’14/15 En–De, De–En); AER | En–De: Baseline LSTM 14.0 → Global 16.8 → +Input Feeding 18.1 → Local-p 19.0 → +UNK repl. 20.9 → Ensemble 23.0 → WMT’15: 25.9 | New SOTA BLEU (25.9), sharp alignments (AER ≈ Berkeley Aligner) |

| Cheng et al. 2016 – LSTMN | Perplexity (PPL), Accuracy (%) | Penn Treebank LM: LSTM PPL 115 → LSTMN: 108 (1-layer), 102 (3-layer); SST Sentiment: 86.4% → 87.0%; SNLI: 83.5% → 86.3% | Better PPL than LSTM, competitive with top CNNs/mLSTMs |

| Wu et al. 2016 – GNMT | BLEU, Human SxS | En–Fr: 38.95 → RL Ensemble 41.16; En–De: 24.61 → 26.30; Human eval: ~60% error reduction vs SMT | Production-ready quality, close to human reference |

| Vaswani et al. 2017 – Transformer | BLEU (WMT’14 En–De, En–Fr), F1 (Parsing) | En–De: 28.4 BLEU (big model), +2 BLEU over best ensemble; En–Fr: 41.8 BLEU (single-model SOTA); Parsing: 91.3–92.7 F1 | First fully attention model, faster + higher BLEU than RNN/CNN |

| Johnson et al. 2017 – Multilingual NMT | BLEU (WMT’14 En–Fr, En–De, Production), Human Eval | Multilingual model matches/surpasses bilingual baselines; enables zero-shot translation (e.g., Ja→Ko) with non-trivial BLEU; human eval shows competitive quality; reduced model count (1 vs thousands) | First multilingual NMT: improved low-resource pairs, enabled zero-shot transfer, evidence of emergent interlingua |

Insights

- Early NMT (Cho, Sutskever): BLEU modestly improved over SMT but crucially handled long/rare phrases better.

- Attention (Bahdanau, Luong): Closed the gap with SMT, competitive BLEU + better alignments.

- Memory-enhanced (LSTMN): Lower perplexity & competitive accuracy across NLP tasks.

- GNMT: Scaled NMT to production, BLEU ~41, major human-level improvements.

- Transformer: Broke performance + efficiency barrier, new gold standard in MT and beyond.

- Multilingual NMT (Johnson et al. 2017): Single model handles many languages, boosts low-resource performance, and enables zero-shot translation — a step toward universal translation.

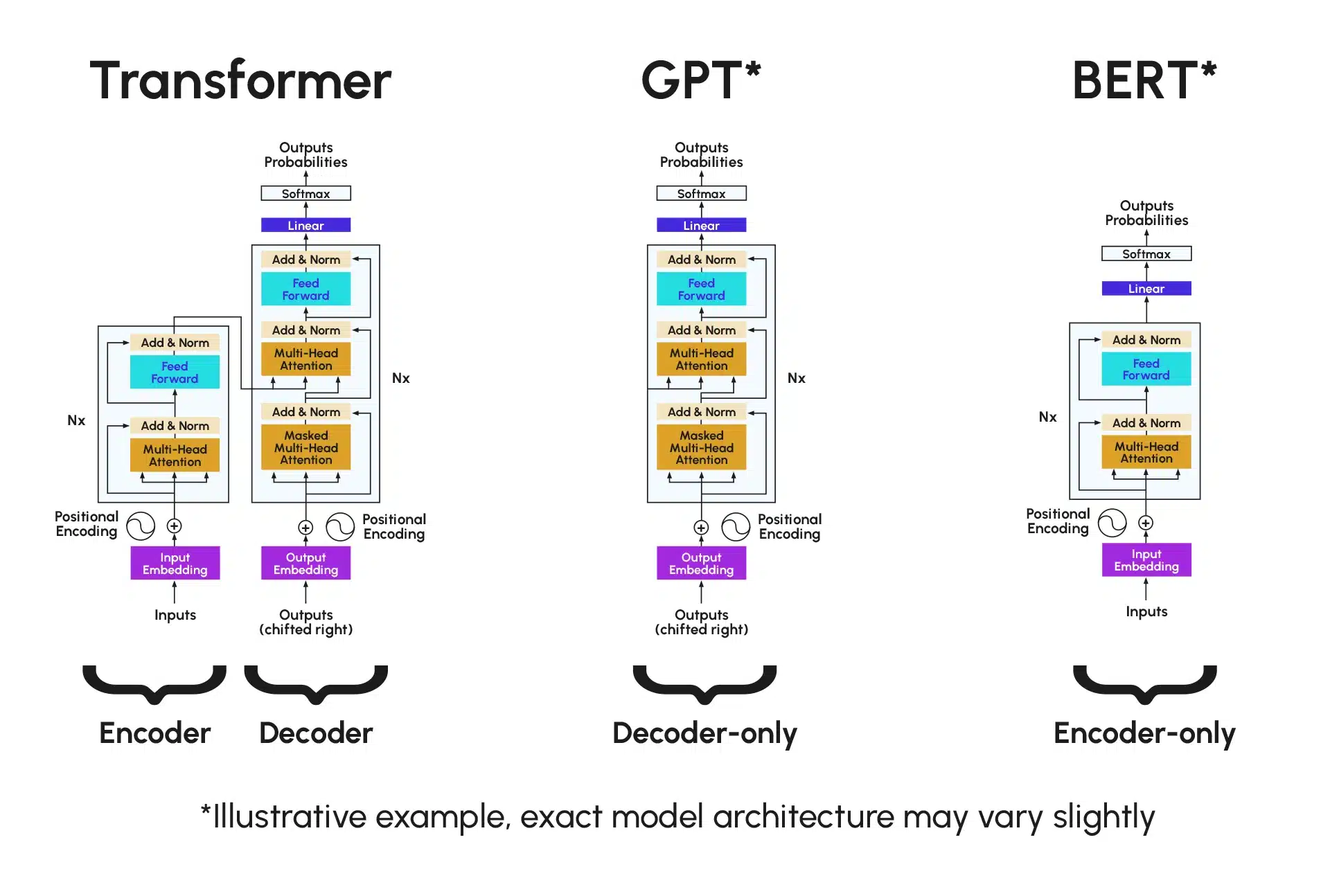

️ Transformer, GPT, and BERT Architectures

These diagrams illustrate the core mechanics of encoder–decoder architectures, the introduction of attention, and the structural differences between landmark Transformer-based models. Sources: Datascientest .

Transformer Explainer Playground *Illustrative example, exact model architectures may vary slightly.

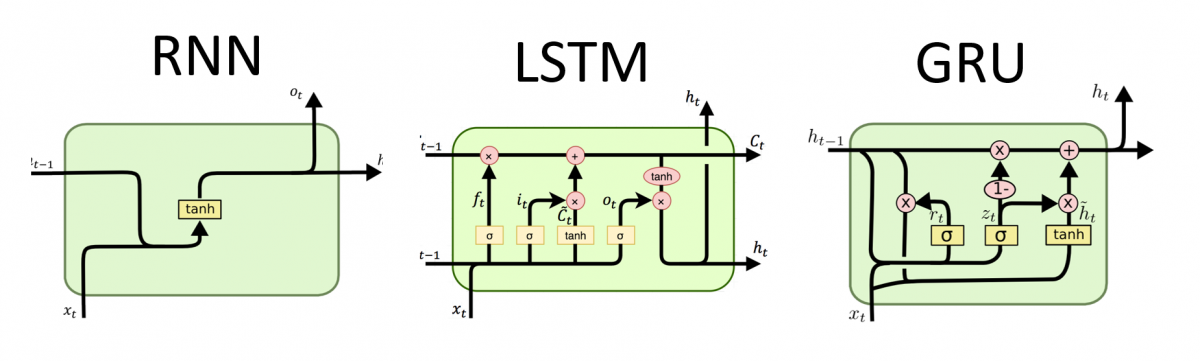

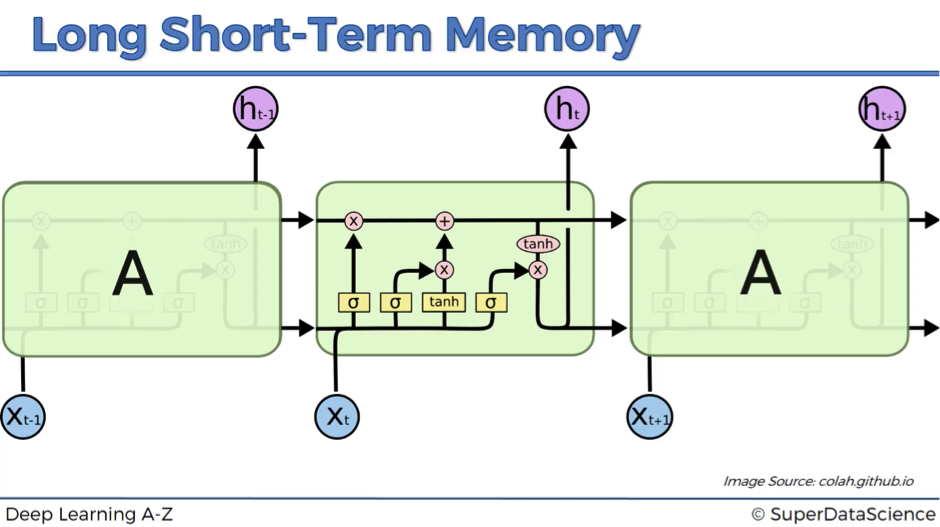

RNN, LSTM & GRU Visual Diagrams

These diagrams illustrate the inner workings of recurrent neural architectures, including the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and a comparative view with vanilla RNNs. Source: SuperDataScience Blog

Comparison: RNN vs LSTM vs GRU

LSTM Sequential Framework

LSTM with Neuron Connections

GRU Cell Architecture

️ Seq2Seq & Attention Visuals

These diagrams illustrate the core mechanics of encoder–decoder architectures and the introduction of attention in neural machine translation. Source: Lena Voita – NLP Course

Encoder–Decoder with Linear Output

Encoder–Decoder Basic Framework

Attention Mechanism in Seq2Seq

LSTM & GRU: Core Equations and Explanations

| MODEL | KEY EQUATIONS / MATH | ILLUSTRATION & EXPLANATION |

|---|---|---|

| Hochreiter & Schmidhuber (1997) – LSTM | \[ f_t = \sigma(W_f [h_{t-1}, x_t] + b_f) \quad \text{(forget gate)} \] \[ i_t = \sigma(W_i [h_{t-1}, x_t] + b_i) \quad \text{(input gate)} \] \[ \tilde{c}_t = \tanh(W_c [h_{t-1}, x_t] + b_c) \quad \text{(candidate)} \] \[ c_t = f_t \odot c_{t-1} + i_t \odot \tilde{c}_t \quad \text{(cell update)} \] \[ o_t = \sigma(W_o [h_{t-1}, x_t] + b_o) \quad \text{(output gate)} \] \[ h_t = o_t \odot \tanh(c_t) \quad \text{(hidden state)} \] |

|

| Cho et al. (2014) – GRU | \[ z_t = \sigma(W_z [h_{t-1}, x_t]) \quad \text{(update gate)} \] \[ r_t = \sigma(W_r [h_{t-1}, x_t]) \quad \text{(reset gate)} \] \[ \tilde{h}_t = \tanh(W_h [r_t \odot h_{t-1}, x_t]) \quad \text{(candidate)} \] \[ h_t = (1 - z_t) \odot h_{t-1} + z_t \odot \tilde{h}_t \quad \text{(hidden state)} \] |

|

Core Equations in MT Papers

| PAPER | KEY EQUATIONS / MATH | CONCEPT |

|---|---|---|

| Cho et al. (2014) – RNN Encoder–Decoder | \[ h_t = f(x_t, h_{t-1}) \] \[ c = q(\{h_1, \dots, h_T\}) \] | Encoder computes hidden states, compresses sequence into fixed-length context vector. |

| Sutskever et al. (2014) – Seq2Seq | \[ p(y) = \prod_{t=1}^T p(y_t \mid y_{< t}, c) \] | Probabilistic decomposition of target sequence given context vector. |

| Bahdanau et al. (2015) – Attention | \[ e_{ij} = a(s_{i-1}, h_j) \] \[ \alpha_{ij} = \frac{\exp(e_{ij})}{\sum_k \exp(e_{ik})} \] \[ c_i = \sum_j \alpha_{ij} h_j \] | Introduced soft alignment (attention) to dynamically weight encoder states. |

| Luong et al. (2015) – Global/Local Attention | \[ c_t = \sum_s \alpha_{ts} h_s \] \[ \alpha_{ts} = \text{softmax}(h_t^\top W h_s) \] | Global = all source positions; Local = predictive window around aligned source. |

| Wu et al. (2016) – GNMT | \[ p(y \mid x) = \prod_{t=1}^T p(y_t \mid y_{< t}, x) \] \[ \text{Beam score:} \quad \frac{\log P(y \mid x)}{\left(5 + |y|\right)^\alpha / \left(5 + 1\right)^\alpha} \] | Scaled RNN NMT, improved decoding with length/coverage penalties. |

| Vaswani et al. (2017) – Transformer | \[ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V \] \[ \text{Multi-Head:} \quad \text{Concat}(\text{head}_i) W^O \] | Replaces recurrence with self-attention; fully parallelizable. |